Take The Polls With A Grain Of Salt

Recently, several polls have given former Vice President Joe Biden a comfortable lead against President Donald Trump. The newest Ipsos/Reuters poll shows Biden leading by as much as 10 points nationally while NPR has changed its ratings of several key states from “toss-up” to “lean Democratic.” There is reason to believe that these polls are accurate. However, given how 2016 went, and the fact that a lot can change before November, we should take these with a grain of salt, even if they seem to confirm the current mainstream outlook of the race.

Polls are far from perfect; if they were, then we would not need voting. The journalist Dan McLaughlin, in a September 2016 article for National Review, wrote that polling is “not an exact science,” but that it is instead an “art.” With that being said, let’s dive into the intricacies which make polling such an imperfect—but essential—art in the world of elections.

2016: What Went Wrong

October 18, 2016: It’s the most intense election in recent memory. We have the two most disliked major-party candidates in modern history. The New York Times, on this day, predicts that Sec. Hillary Clinton has a 91-percent chance of winning the election.

The Times wasn’t alone in predicting that Clinton would win. Even some big-name Republicans publicly expressed their hesitance to back the very controversial Trump, doubting that he could beat Clinton. When asked if Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse would attend the 2016 Republican National Convention, his spokesperson stated: “Sen. Sasse will not be attending the convention and will instead take his kids to watch some dumpster fires across the state, all of which enjoy more popularity than the current front-runners.”

However, we all know how this tale ends. In the fallout of Trump’s victory, the media was heavily criticized for getting their polls wrong.

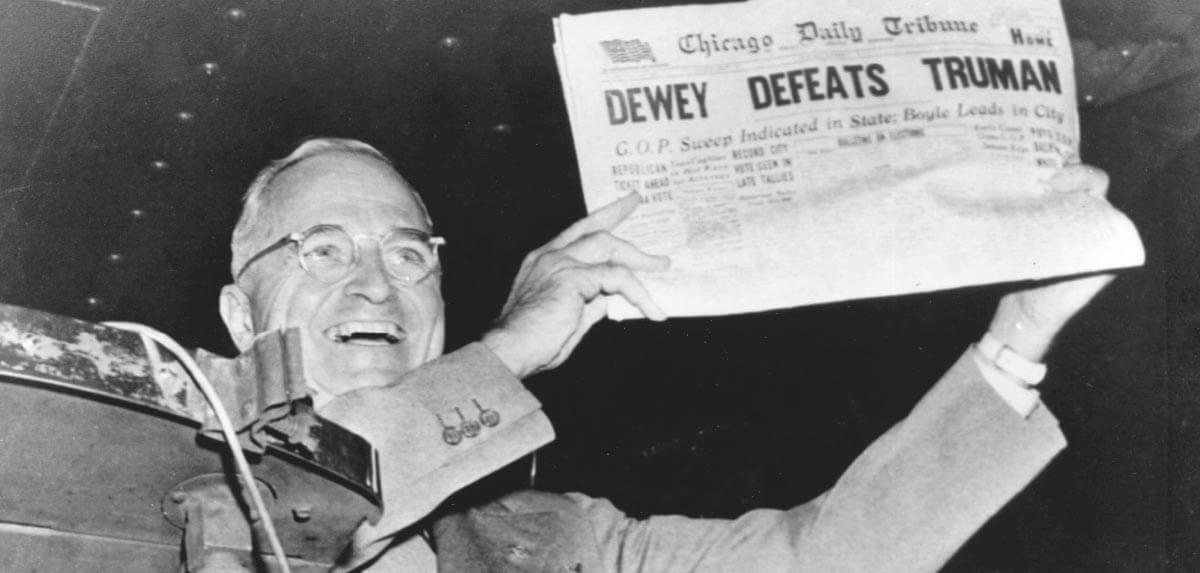

Aside from 2000, the only modern election comparable to this was 1948. The evening of the vote, before the East Coast results were even reported, the Chicago Daily Tribune infamously predicted that Thomas Dewey would defeat then-incumbent President Harry Truman. The paper was incorrect, to say the least. The only upside to this error was that it gifted us with this iconic image of Truman holding up the wrong headline (below).

All of this begs the question: If the polls got it wrong in mid-October 2016, how can we expect them to get it right in early August 2020?

In the lead-up to the 2020 election, many commentators and voters alike have expressed skepticism of the polls—and rightly so. A significant criticism lobbed at pollsters has been that they failed to account for conservative voters who were too afraid to admit that they were voting for the polarizing Trump. As a result, this downplayed his support. This is the dominant theory for why the polls were wrong in 2016 that commentators and voters alike have clung to.

The 2018 Midterms: Recalibration

The pollsters, however, redeemed themselves in 2018. Polling analytics company FiveThirtyEight, for example, was only off by a margin of two House seats for the Democrats in its final pre-results forecast for 2018. This is an improvement from their final 2016 election forecast, which predicted that Clinton would win. FiveThirtyEight’s editor-in-chief and founder, Nate Silver, defends their 2016 prediction, saying that they “gave Trump a better chance than almost anyone else.” He goes further, adding that “our final forecast [...] had Trump with a 29 percent chance of winning the Electoral College. By comparison, other models tracked by The New York Times put Trump’s odds at: 15 percent, 8 percent, 2 percent and less than 1 percent.”

Though, midterm elections differ from presidential ones in many regards, requiring pollsters to use a different methodology.

All midterm elections are decided by a popular vote and happen exclusively at the state, congressional, and local levels. The popular vote keeps the process relatively straightforward, but new challenges arise from the sheer amount of important races to track and from the wild variation of rules and regulations between each state. While every midterm election features a staggering 435 U.S. House races, thirty-something Senate ones, and many gubernatorial ones, many races’ outcomes are quite predictable. Understandably, these receive less attention than their more competitive ‘battleground’ counterparts. (And this is only the general election, mind you.)

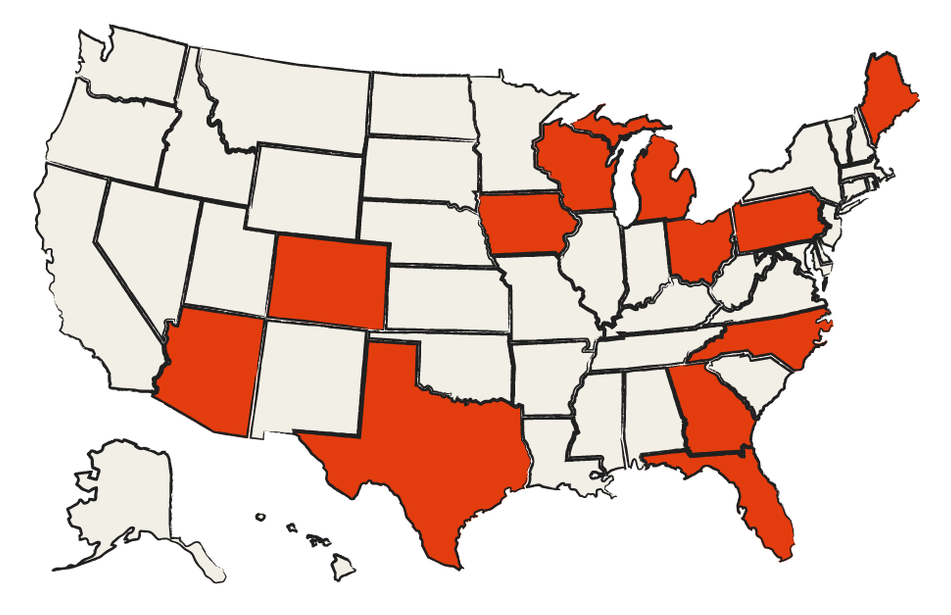

Presidential elections, on the other hand, have their own sets of rules and factors. Similar to House and Senate races, presidential ones take place across the entire country. And just how there are House and Senate races that are bound to go one way, there are individual states that are almost certain to swing for one party over the other. However, the Electoral College complicates this. Unlike House and Senate races, presidential races are not determined by a popular vote. Instead, whoever wins the popular vote in a given state will receive all of that state’s Electoral College votes (except for Nebraska and Maine). Rinse and repeat in all 50 states (plus the District of Columbia). In the end, whoever has the most electoral votes wins the whole kit and caboodle—even if you don’t win the national popular vote or have the majority of electoral votes.

Thus, much of what goes into predicting the outcomes of presidential elections relies on zeroing in on these ‘battleground’ states, accounting for intrastate regional and demographic differences, and ensuring that the voters in the sample polled are reflective of their state’s make-up. Even still, after all of this intense labor, performed over and over again until Election Day, the results are not guaranteed to be accurate.

The Here-and-Now

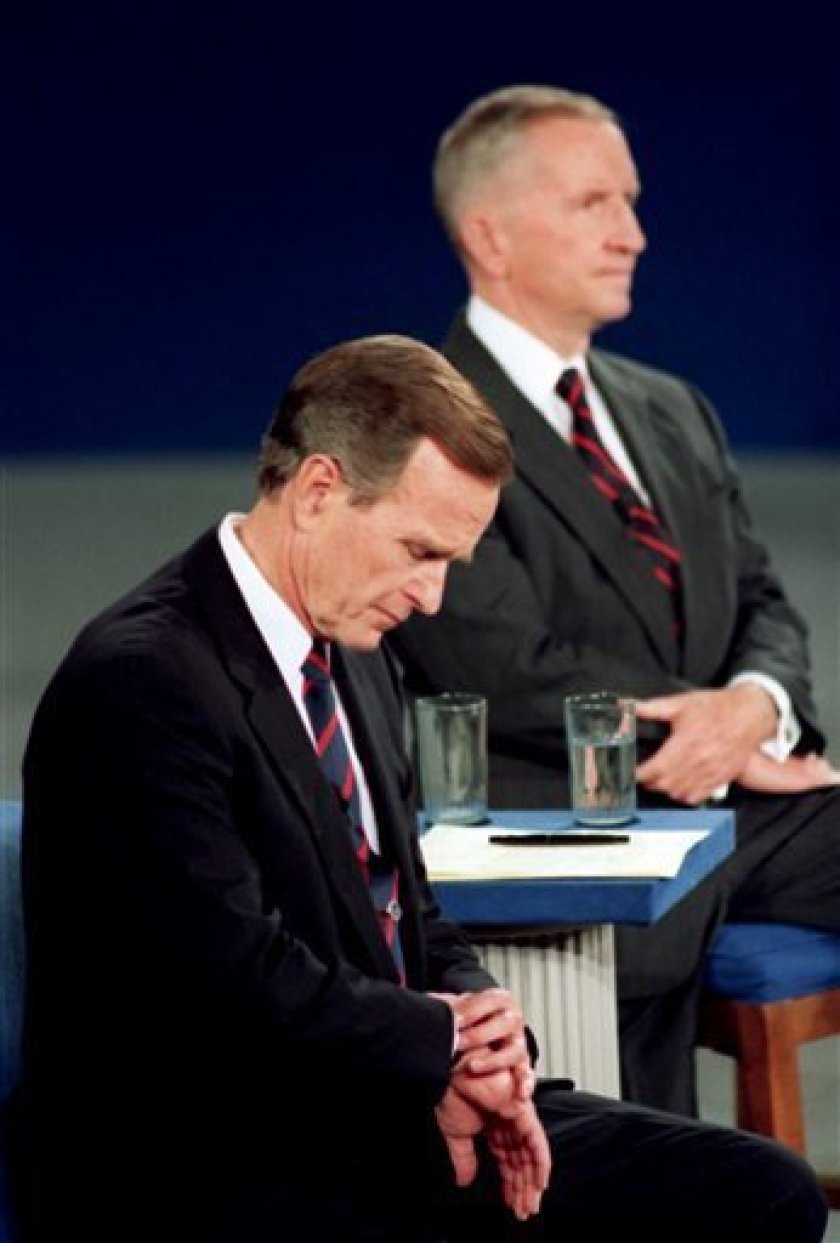

This brings us to the present. As of Friday, we are 88 days away from Election Day, and two potentially game-changing events have not occurred yet. Firstly, Biden plans to announce his running mate sometime before the Democratic National Convention starts on August 17. The big what-if is how the progressive wing of the Democratic Party will respond to his choice, which could potentially affect turnout in states where the candidates are neck and neck. Then lastly, and most importantly, we will not see Trump and Biden square off on the national debate stage until late next month. The debates are particularly critical because poor (or great) debate performances have historically impacted elections results to some degree. As mentioned earlier, Biden holds a big lead over Trump in the polls. However, Biden has been openly mocked by both Republicans and Democrats for his rusty mental acuity, jumbled and slurred speech, and his detailed history of making gaffes.

Mind you, this is all without mentioning the prospect of a deadly ‘October surprise.’ October surprises are dramatic and sudden events or revelations. These most often have the potential to either ruin the reputation of a candidate (e.g. FBI Director James Comey announcing the re-opening of the investigation of Hillary Clinton’s email, the leaked ‘Access Hollywood’ tape of Donald Trump) or directly impact the lives of millions of voters (e.g. the 2008 Stock Market Crisis, Hurricane Sandy).

It goes without saying that it is too early to predict the results of the upcoming election accurately. Seeing how unpredictably eventful this year has been so far, we should remain cautious. Despite all this, polls do hold some use, in that they give everyone, especially experts, a sense of the country’s pulse at any given moment.

This circles us back to Dan McLaughlin. “Polls, in the aggregate, are fairly effective at what they do,” he wrote in the same 2016 article, “but they also tend to project a false sense of precision in an imprecise business.”

And, in the spirit of this article’s title, please take what I have written, too, with a grain of salt.